Luck and Avoiding Avalanches

The Avalanche Review printed this article in spring 2024. Minor revisions here.

The next skier triggers the entire face. Conditions and partners align to make skiing in extreme terrain feel easy. The local avalanche guru dies in an avalanche. As Gallatin Avalanche Center director Doug Chabot says, “Luck is real, both good luck and bad luck.”

Luck can be defined as a chance occurrence that affects us. Luck is out of our control and unpredictable. What we can do is improve skill, which minimizes luck. Understanding this need to improve skill and reduce luck is important because avoiding avalanches does involve luck.

How Much Luck is Involved with Avoiding Avalanches?

In Michael Mauboussin’s book The Success Equation (Mauboussin 2012), he writes, “When a measure of luck is involved, a good process will have a good outcome but only over time.” Cause and effect are loosely linked in the short run. By that description, avoiding avalanches includes luck. Over a few tours or a season, an amateur may trigger as many unintentional avalanches as a professional, but over the long haul a professional will trigger less unintentional avalanches for the number of days out.

Mauboussin also describes how to test whether an activity includes luck. “Ask whether you can lose on purpose. In games of skill it’s clear you can lose intentionally, but when playing roulette or the lottery you can’t lose on purpose.” By that test, avoiding avalanches includes some luck because you can’t always lose (get avalanched) on purpose.

“The lion tamer has the book on lion taming. She goes into the cage and she does everything by the book, but she still gets eaten by the lion.”

Using myself as an example, I have spent decades working at improving my avalanche-avoidance skills, but luck is still involved. Although I have never been avalanched, I have unintentionally started many avalanches, a client of mine was avalanched and not hurt, and my climbing partner was killed by an avalanche. All of these can be viewed as combinations of good skill, poor skill, good luck, and bad luck.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Our experiences with avalanches can be difficult to understand and seem random. For example, an avalanche accident involving friends, or deep slab avalanches can appear as random outliers. The human mind creates cause and effect stories to simplify and better understand these complex experiences, just like everything we don’t truly understand. This pattern seeking is called the narrative fallacy. I didn’t trigger the deep slab because….

In addition to not understanding seemingly random events, the human mind also does poorly at understanding probabilities. The gambler’s fallacy is another narrative we tell ourselves in which we equate a random string of good luck to skill. Say we nail five days of skiing with stable snow, stable weather, and stable partners. Was that skill like we tend to think, or did we get lucky?

An important way of thinking about probabilities is that above average outcomes tend to be followed by events that are more average. “Any activity that combines skill and luck will eventually revert to the mean,” says Maubuossin. For example, you may have good luck and ski many days in avalanche terrain during considerable avalanche danger. Reversion to the mean explains that your good luck will probably run out since the average likelihood for considerable danger is “human-triggered avalanches likely.”

“Skill and experience are how you change probabilities. Luck determines what side of the probability you fall on. ”

Luck-Skill-Continuum

Gaining knowledge and experience don’t improve our luck. They improve our skill. Our ability to avoid avalanches lies on a luck-skill continuum. At one end of the spectrum are avalanche amateurs who rely more on luck. At the other end are professionals who rely more on skill, although they take on more lifetime risk. The important thing to consider is where your actions lie on this luck-skill spectrum. Then you can shift your actions and training to reduce luck, and move toward skill. It’s still a combination, though. One can be skilled and get lucky, or skilled and unlucky.

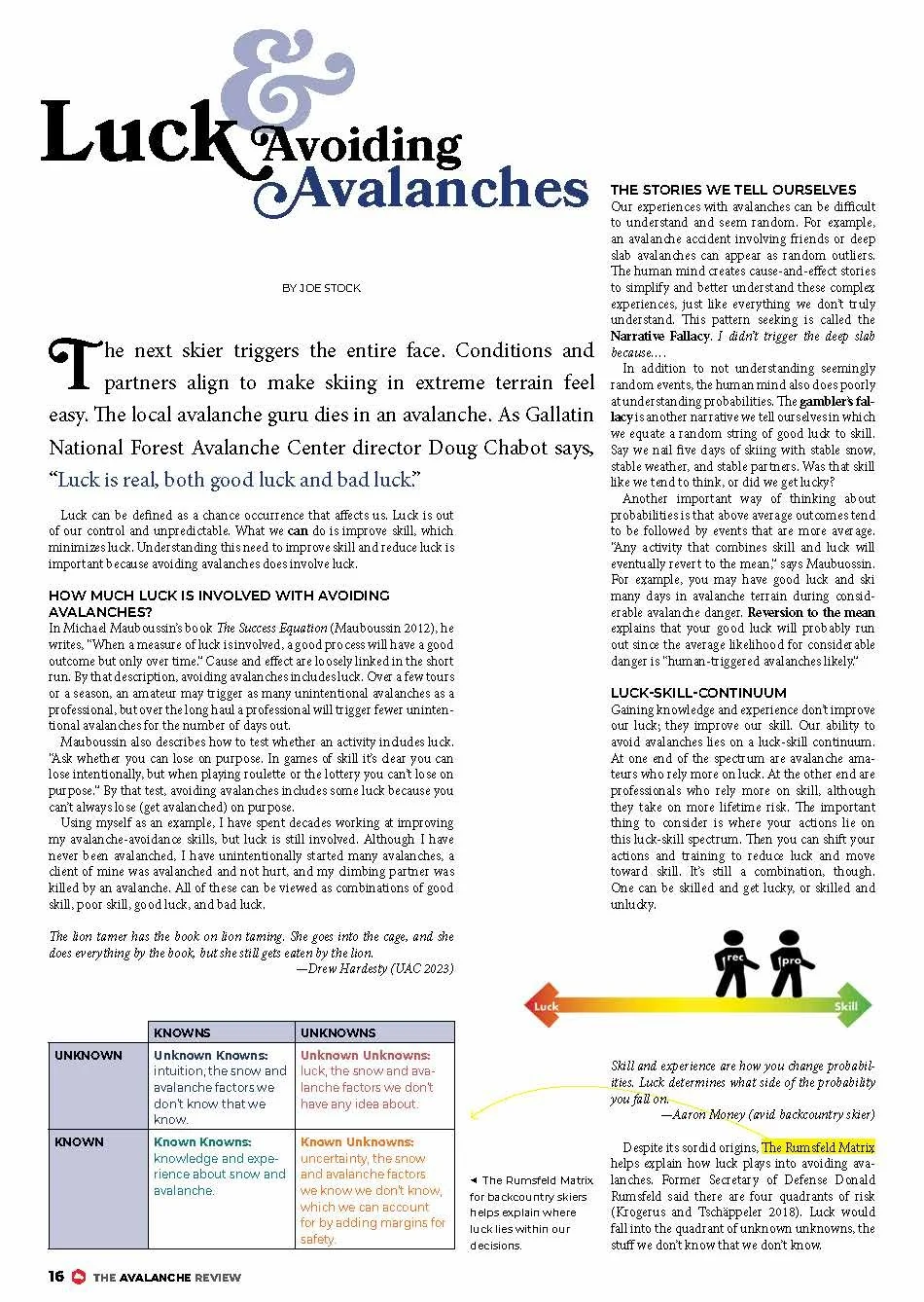

Despite its sordid origins, The Rumsfeld Matrix helps explain how luck plays into avoiding avalanches. Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said there are four quadrants of risk (Krogerus and Tschäppeler 2018). Luck would fall into the quadrant of unknown unknowns, the stuff we don’t know that we don’t know.

The Rumsfeld Matrix for backcountry skiers helps explain where luck lies within our decisions.

The Rumsfeld Matrix can be viewed on a bar graph with ranges for amateurs and professionals in avalanche terrain. The amateur relies more on luck. The professional relies more on knowledge, experience, and intuition. Neuroscience professor and backcountry skier Russ Costa says, “I think about it as uncertainty reduction, and the uncertainty that remains (there's always some) is luck.”

Amateurs rely more on luck than professionals. Professionals rely more on knowledge, experience, and intuition.

Bayesian updating is a useful way to describe a shift from luck to skill. Say the avalanche forecast danger is moderate for a storm slab problem, so you plan to ski in challenging terrain. Once in the field you notice numerous recent avalanches. Rather than staying on challenging terrain and relying on luck, or giving up and going home, you update your prior knowledge with this new information and change the slope-scale danger from moderate to considerable, and shift from challenging to simple terrain.

Improve Your Skill, Reduce Your Luck

When people say, “It all comes down to luck,” it prevents them from learning. As National Avalanche Center specialist Chris Lundy says (UAC 2023), “Luck in the backcountry is what makes it hard to develop expertise.” The wicked learning environment is due to the effect of luck on avalanche decisions. Luck in the complex avalanche environment creates unjustified confidence in those who are less skilled and experiencing good luck, and unjustified doubt in those who are skilled and experiencing bad luck. This makes avalanche expertise only attainable through a combination of experience and deliberate practice to learn the right lessons. Experience alone doesn’t develop avalanche expertise. Chabot says, “What we can control is being trained, fit and skilled so we can minimize the bad luck (he's buried and I have to dig him out fast), and maximize good luck (the slopes are more stable than I thought).”

Focus on the Process, Not the Outcome

With help from the Narrative Fallacy, we often confuse skill and luck. Our initial reaction to hearing about an accident is, I wouldn’t have done that, and use the explanation of Their poor skill, as a way to simplify and understand those mistakes. This self-serving bias also leads us to believe that I made all the right decisions, but then got unlucky. These ways of thinking about luck and skill fit into a process-outcome matrix (Parrish 2023).

Our confusion with skill and luck can be seen in a Process-Outcome Matrix (Parrish 2023).

“Amateurs focus on the outcome. Professionals focus on the process.”

In environments that involve luck, a good outcome (eg. not getting avalanched) does not mean the process (eg. making observations) was good. “In activities where luck plays a strong role, the focus must be on process….where luck is a strong force, the link between process and outcome is broken.” says Mauboussin. In Clear Thinking (Parrish 2023) Shane Parrish calls it “The Process Principle: When you evaluate a decision, focus on the process you used to make the decision and not the outcome.” Improve process by gaining knowledge, experience, practice, and debriefing to learn the right lessons. Below are some ways to focus on the process to improve your skill and reduce your luck.

How to Improve Your Skill and Reduce your Luck

1. Debrief. By acknowledging when you were lucky, you can better perceive those situations in the future and adjust course. Debrief at the end of the day to examine your sense- and decision-making process separate from the outcome. Beers and high fives alone don’t count. Asking “Did we get lucky today?” is a good debrief question.

2. Don’t push your luck. Lucky streaks will end as the outcomes revert to the mean. Say you’ve started ski cutting large avalanches in the backcountry without being caught. Pushing your luck with a wild snowpack will eventually revert to the mean, which means getting avalanched.

3. Be prepared for good luck. If you get the ball, do you know which way to run? Arm yourself with a quiver of trips for when weather, snowpack, and partners align. Get advanced avalanche training and practice those skills so you’re in position when a potentially great new backcountry partner comes along.

4. Be prepared for bad luck. Consider the consequences of bad luck. If the slope avalanches will I be okay or will I be dead? Make yourself lucky by choosing terrain that has an escape zone and a good runout, so if it avalanches the outcome isn’t “he was unlucky to die,” and is instead “he got lucky to not get buried.” Likewise, train for bad luck by practicing wilderness first aid, avalanche rescue, shelter building, fire building, sled evacuation, etc.

5. Learn from other’s bad luck. Fight your instinctive temptation to think, I wouldn’t have done that. Rather than attributing someone else’s accident to their poor skill, see what you can learn from their experience. Put yourself in their shoes, without the hindsight benefit of knowing about the avalanche.

References

Chris Lundy on the Four-Letter Word of Decision Making. Utah Avalanche Center Podcast. January 23, 2023.

Mikael Krogerus and Roman Tschäppeler. The Decision Book. 2018.

Michael Mauboussin. The Success Equation. 2012.

Shane Parrish. Turning Pro: The Difference Between Amateurs and Professionals. Farnam Street blog, accessed February 25, 2024.

Shane Parrish. Clear Thinking. 2023.

The Avalanche Review. Are We Good or Just Lucky? 36.3. 2018.

Thank you for helping with this article

Aaron Money, Andrew Schauer, Bruce Tremper, Cathy Flanagan, Chris Lundy, Clint Schmidt, Doug Chabot, Lynne Wolfe, Mark Smiley, and Russ Costa.